UPDATED 19 MARCH 2020:

In January, risk #5 described how Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his government revoked the special status of Jammu and Kashmir, piloted a plan that stripped 1.9 million people of their citizenship, and passed an immigration law that considers religious affiliation. As protests of various kinds expanded across India, Modi would not back down, we warned, and a harsh government response in 2020 would provoke more demonstrations. Meanwhile, emboldened state-level opposition leaders would directly challenge the central government, leaving Modi with less room for maneuver on economic reform at a time of slowing growth.

With a population density nearly three times that of China, a weaker health and sanitation infrastructure, and a far less autocratic government, India is acutely vulnerable to a coronavirus outbreak. So far, it has handled it well—the Indian government was one of the first to impose draconian border measures, with no foreign tourists allowed to enter the country until at least 15 April. But the challenges for India going forward will only increase. There is a significant risk that misinformation about the coronavirus will be targeted at minority communities and/or sow confusion, possibly sparking sectarian violence. The financial stress for India and emerging markets generally will offset benefits from the drop in oil prices. India is likely to see significant capital outflows, currency devaluation, and renewed urgency for economic reforms. However, those reforms are unlikely to happen, as Modi's economic team is still dominated by statists, and the government will continue to prioritize its nationalist agenda over reforms.

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED 6 JANUARY 2020:

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED 6 JANUARY 2020:

PRIME MINISTER NARENDRA MODI HAS SPENT MUCH OF HIS SECOND TERM PROMOTING CONTROVERSIAL SOCIAL POLICIES AT THE EXPENSE OF AN ECONOMIC AGENDA. The impacts will be felt in 2020, with intensified communal and sectarian instability, as well as foreign policy and economic setbacks.

Modi and his government have been busy in recent months. They revoked the special status for Jammu and Kashmir and implemented a system to identify illegal immigrants in the northeast, stripping 1.9 million people of citizenship. The government also passed a law that, for the first time, makes religion a criterion for migrants from neighboring countries to formally acquire Indian citizenship. Behind these moves is Amit Shah, the former head of Modi's Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), now home minister.

Sectarian and religious conflict will grow accordingly. Kashmir is a powder keg, with political leaders still under arrest and internet access cut off. Protests have already spread around India as many citizens fear the loss of India's secular identity. The government's harsh response, in turn, will provoke still more demonstrations. But Modi will not back down, and as the government pursues its new agenda, state-level opposition leaders will directly challenge the central government.

This focus on the social agenda will also have harmful effects for India's foreign policy. Its actions on human rights will be under closer scrutiny by many nations, and its reputation will take a hit. India's relations with the US, which have been a bright spot under Modi, will face a challenge in 2020. Some members of the US Congress are concerned with India's policies generally, and in particular with its plans to buy the S-400 missile defense system from Russia. Congress could impose sanctions. At the least, the anti-missile system purchase will impede further sales of US military equipment to India, the strongest plank of the bilateral relationship.

Sectarian and religious conflict will grow this year.

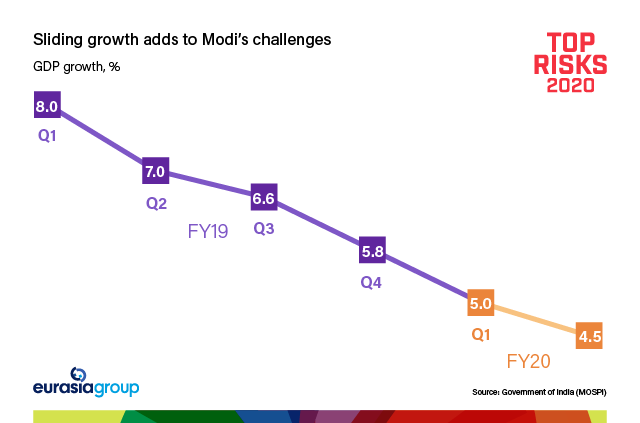

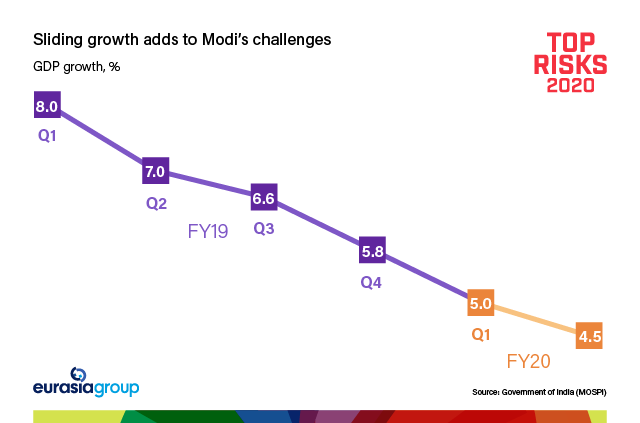

The economic spillover is also noteworthy. The social agenda has empowered a key part of Modi's base, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS)—Hindu nationalists who oppose market opening and support economic nationalism. The RSS is the ideological parent to Modi's BJP and helped ensure his reelection. An empowered RSS means that Modi has less room to maneuver on structural reforms, just as the economy is starting to sputter, with quarterly growth falling to a six-year low of 4.5% and forward-looking indicators looking softer still. The RSS influence was evident in Modi's decision to drop out of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership negotiations last year and will be a big reason why India is unlikely to rejoin in 2020.

India's fiscal situation is also precarious, as the government faces a widening fiscal deficit, marked by the underperformance of the goods and services tax. A weakened economy will in turn feed further economic nationalism and protectionism, weighing on India's troubled course in 2020.