The time has come to update our Top Risks 2020, taking into account how the coronavirus has accelerated the trends that worry us most.

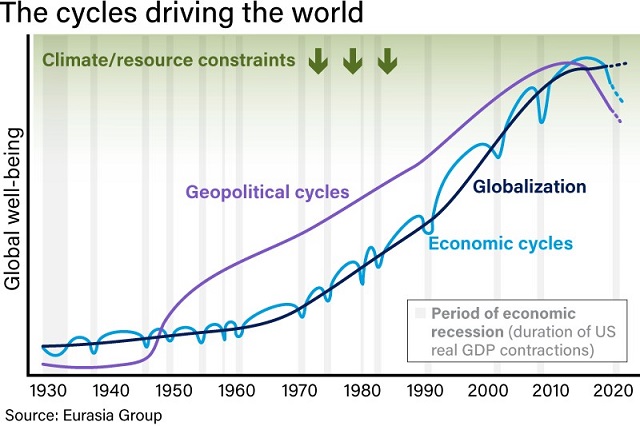

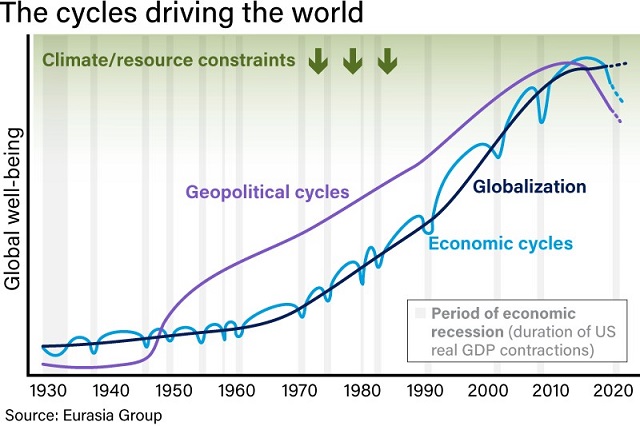

INTRODUCTIONIn January, we wrote that this year was a tipping point, with a historic shift in globalization; a weakened US leadership; the rise of populism within the world's democracies; the rise of an alternative Chinese economic, political and technological model; and the decline of an aggrieved and interventionist Russia pushing the world into a geopolitical recession. We now face the first global crisis of our geopolitical recession … a coronavirus pandemic. The timing isn't good.

We warned in January that globalization was under siege; we were more right about that than we would like to be. Travel to the US from Europe and China, and travel to Europe from just about anywhere, has now been halted. The coronavirus outbreak has dealt a body blow to the global flow of goods and services, accelerating the process we wrote about. The public health emergency has also deepened the geopolitical recession, as the US shows little interest in quarterbacking an international response, and China aims to take advantage of the vacuum. More broadly, the pandemic has forced all nations to look inward, speeding both this recession and the process of deglobalization.

In January, risk #1 described how US institutions would be tested as never before, and how the November election would produce a result many would see as illegitimate. If President Donald Trump won amid credible charges of irregularities, the results would be contested. If he lost, particularly if the vote was close, same. Either scenario would create months of lawsuits and a political vacuum, but unlike the contested George W. Bush-Al Gore election of 2000, the loser was unlikely to accept a court-decided outcome as legitimate. It was a US version of Brexit, where the issue wasn't the outcome but political uncertainty about what people had voted for.

In January, risk #1 described how US institutions would be tested as never before, and how the November election would produce a result many would see as illegitimate. If President Donald Trump won amid credible charges of irregularities, the results would be contested. If he lost, particularly if the vote was close, same. Either scenario would create months of lawsuits and a political vacuum, but unlike the contested George W. Bush-Al Gore election of 2000, the loser was unlikely to accept a court-decided outcome as legitimate. It was a US version of Brexit, where the issue wasn't the outcome but political uncertainty about what people had voted for.

The coronavirus outbreak heightens these risks and brings them forward. Georgia, Louisiana, Kentucky, and Ohio are the first states to delay their primaries due to coronavirus fears, and they surely won't be the last. Many voters won't feel safe casting a ballot in person, a fear that will be amplified by misinformation.

As the administration's handling of the coronavirus outbreak continues to attract criticism, and the economy tumbles into recession, Trump will be tempted to sow doubts about the integrity of the election, not to mention aggressively going after presumptive Democratic nominee Joe Biden and his son Hunter. Health fears and rumors about the likely Democratic nominee are already being weaponized for political ends, and politicized investigations are likely. Meanwhile class tensions will be exacerbated, with many blue-collar workers unable to easily work from home, school cancelations wreaking havoc on poor and single-parent families, and possible violence and disruptions over access to both public and private medical care. Already, generational divides are sharpening, with many young Americans, at lower risk of dying from the coronavirus, defying orders for “social distancing.” The run-up to this election will be the most divisive in modern history.

As the campaign season progresses, a candidate trailing in the polls could play on social anxiety to call for a delay in the vote—even if the date is legally very difficult to change because it would require legislation that could win approval from Congress, the president, and the courts. More likely, states could shift most voting from in person to absentee paper and/or online ballots. This approach would bring new risks. There is currently no plan B for an election that can't have people voting at polls. If states turn to the mail, can it be done securely, will it structurally favor one side, and will that tempt one or both candidates to undermine its credibility? If the US goes to e-voting, nefarious actors will see greater opportunity to disrupt the process. Even without malign interference, all it would take is a technical glitch to call the results into question. Who would it help? No one knows, which is exactly our point.

After the election, the vote could be contested on grounds of tampering, procedural flaws, and/or historically low turnout. Whoever wins would lack full authority in the eyes of Americans and the international community. The US Congress could become even more dysfunctional than we expected in January, not least because of teething pains as it learns to work remotely—all amid a crisis over the vote. Finally, on foreign policy, the coronavirus will cause the US to turn inward and increase its isolation from the world. Less US leadership and reassurance to allies will be the result.

.jpg)

In January, risk #2 described how the decoupling of the US and Chinese tech sectors was already disrupting bilateral flows of technology, talent, and investment. In 2020, we argued that this decoupling would move beyond strategic tech sectors such as semiconductors, cloud computing, and 5G into broader economic activity. This trend would affect not just the $5 trillion global tech sector, but other industries and institutions as well. It would create a deepening business, economic, and cultural divide that risks becoming permanent, casting a deep geopolitical chill over global business. The big question we asked back in January: Where would the virtual Berlin Wall stand?

In January, risk #2 described how the decoupling of the US and Chinese tech sectors was already disrupting bilateral flows of technology, talent, and investment. In 2020, we argued that this decoupling would move beyond strategic tech sectors such as semiconductors, cloud computing, and 5G into broader economic activity. This trend would affect not just the $5 trillion global tech sector, but other industries and institutions as well. It would create a deepening business, economic, and cultural divide that risks becoming permanent, casting a deep geopolitical chill over global business. The big question we asked back in January: Where would the virtual Berlin Wall stand?

Decoupling between the US and China was marching ahead before the coronavirus outbreak, spreading from the technology sector to arenas such as finance and scientific cooperation. But the coronavirus has dramatically accelerated and extended this trend to the manufacturing and services sectors, forcing many companies to rapidly switch supply chains, close facilities, and move staff. Public health restrictions have halted routine travel between the US and China, stifling cooperation and exchange. Corporations will face hard choices. Do they permanently move supply chains away from China, now that events have demonstrated the risk of over-concentrating production? Or do they stay in China but build costly redundancies? Policymakers in the US and elsewhere will have their say, with many using the crisis to argue that production must move closer to home. Trends of broader decoupling between the world's two largest economies will become more, not less, deeply entrenched as a result of the coronavirus, while other countries will experience greater challenges in balancing relations with both sides.

In January, risk #3 argued that as US-China decoupling occurred, tensions would provoke a more explicit clash over national security, influence, and values. The two sides would continue to use economic tools in this struggle—sanctions, export controls, and boycotts—with shorter fuses and goals that were more explicitly political. Confrontation would grow over Hong Kong, Taiwan, the Uighurs, the South China Sea, and a host of other issues.

In January, risk #3 argued that as US-China decoupling occurred, tensions would provoke a more explicit clash over national security, influence, and values. The two sides would continue to use economic tools in this struggle—sanctions, export controls, and boycotts—with shorter fuses and goals that were more explicitly political. Confrontation would grow over Hong Kong, Taiwan, the Uighurs, the South China Sea, and a host of other issues.

Washington and Beijing view the outbreak as the next round in their geopolitical rivalry, and that dynamic will continue to shape the global response to the crisis. US officials blame Beijing for causing what they pointedly call the “Chinese” coronavirus and are wary of emergency coronavirus funds from the IMF being used to repay countries' debts to China under the Belt and Road Initiative. Beijing, eager to counter US criticism, will use its success at coronavirus containment to tout its governance model. It will provide financial and medical assistance to friendly countries (including more and more US allies) channeled, when possible, via its own currency and through Chinese-led institutions. As the election nears, a defensive Trump will deflect criticism of his handling of the outbreak by heaping more blame on China, while more confident Chinese authorities will respond in kind (recent moves by Beijing to ban US journalists from the mainland and Hong Kong are particularly noteworthy on that count). Escalating tensions will create more uncertainty around the phase one trade deal, US treatment of Huawei and other Chinese tech firms, and foreign policy flashpoints such as Hong Kong and Taiwan. All this means that a phase two trade deal is nearly impossible, and escalating tensions could unravel the phase one deal itself. There's a growing likelihood that when the coronavirus pandemic is over, the US and China enter a new cold war.

In January, our risk #4 described how multinational corporations (MNCs), far from compensating for the shortcomings of underperforming national governments on critical issues such as climate change, poverty reduction, and trade liberalization, would face new pressures from political officials, both elected and unelected. Politicians working to manage slowing global growth, widening inequality, mounting populist threats, and intensifying security challenges created by new technologies would assert themselves at the expense of MNCs. In this more difficult global environment, corporate leaders would be more focused on their bottom lines, not less.

In January, our risk #4 described how multinational corporations (MNCs), far from compensating for the shortcomings of underperforming national governments on critical issues such as climate change, poverty reduction, and trade liberalization, would face new pressures from political officials, both elected and unelected. Politicians working to manage slowing global growth, widening inequality, mounting populist threats, and intensifying security challenges created by new technologies would assert themselves at the expense of MNCs. In this more difficult global environment, corporate leaders would be more focused on their bottom lines, not less.

Multinational corporations are already hit hard by the outbreak. Economic stimulus will dominate the geo-economic landscape, and that will frequently mean higher taxes on MNCs and other entities to pay for them. Health-focused regulations will increase dramatically, raising costs. And the outbreak will force MNCs to shorten supply chains, build redundancies, and manage a virtual work force—a recipe for financial and management stresses. But it's not all bad news. With governments consumed by public health crises, there will be little bandwidth for aggressive tech regulation initiatives, for example. And many MNCs will have an opportunity to step up and play leadership roles as governments falter, whether by helping officials conduct coronavirus testing or by developing new teleworking and paid sick leave practices.

In January, risk #5 described how Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his government revoked the special status of Jammu and Kashmir, piloted a plan that stripped 1.9 million people of their citizenship, and passed an immigration law that considers religious affiliation. As protests of various kinds expanded across India, Modi would not back down, we warned, and a harsh government response in 2020 would provoke more demonstrations. Meanwhile, emboldened state-level opposition leaders would directly challenge the central government, leaving Modi with less room for maneuver on economic reform at a time of slowing growth.

In January, risk #5 described how Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his government revoked the special status of Jammu and Kashmir, piloted a plan that stripped 1.9 million people of their citizenship, and passed an immigration law that considers religious affiliation. As protests of various kinds expanded across India, Modi would not back down, we warned, and a harsh government response in 2020 would provoke more demonstrations. Meanwhile, emboldened state-level opposition leaders would directly challenge the central government, leaving Modi with less room for maneuver on economic reform at a time of slowing growth.

With a population density nearly three times that of China, a weaker health and sanitation infrastructure, and a far less autocratic government, India is acutely vulnerable to a coronavirus outbreak. So far, it has handled it well—the Indian government was one of the first to impose draconian border measures, with no foreign tourists allowed to enter the country until at least 15 April. But the challenges for India going forward will only increase. There is a significant risk that misinformation about the coronavirus will be targeted at minority communities and/or sow confusion, possibly sparking sectarian violence. The financial stress for India and emerging markets generally will offset benefits from the drop in oil prices. India is likely to see significant capital outflows, currency devaluation, and renewed urgency for economic reforms. However, those reforms are unlikely to happen, as Modi's economic team is still dominated by statists, and the government will continue to prioritize its nationalist agenda over reforms.

In January, risk #6 described how the European Union aimed to defend itself more aggressively against competing economic and political blocs. On regulation, antitrust officials would continue to battle North American tech giants. On trade, the EU would become more assertive on rules enforcement and retaliatory tariffs. On security, officials would try to use the world's largest market to break down cross-border barriers to military trade and tech development. This more independent Europe would generate friction with both the US and China.

In January, risk #6 described how the European Union aimed to defend itself more aggressively against competing economic and political blocs. On regulation, antitrust officials would continue to battle North American tech giants. On trade, the EU would become more assertive on rules enforcement and retaliatory tariffs. On security, officials would try to use the world's largest market to break down cross-border barriers to military trade and tech development. This more independent Europe would generate friction with both the US and China.

Individual European governments have been late to react to the coronavirus crisis, which is pushing the EU to become more cohesive and act as the critical backstop for the continent. Authorities in Brussels have given Italy more fiscal room to reduce risk and provided both fiscal stimulus and budgetary flexibility with strong agreement among all member states. Trump's decision to target Europe for travel restrictions will strongly encourage the trend toward more independence and increase the transatlantic strains we wrote about in January. If the EU successfully manages the coronavirus response, its leaders may become bolder in pursuing a more independent geopolitical policy. But that's a big if, especially given the likelihood of recession over the coming months. And should that recession be deeper or longer than currently expected, a Europe with a depleted monetary policy toolkit and no shortage of political obstacles to large-scale fiscal stimulus could face a “lost decade” a la Japan. Either way, the pandemic will also blunt some of the other implications of a geopolitical Europe, most notably a more aggressive posture toward Beijing, which is implausible in this environment.

In January, risk #7 described how climate change would put governments, investors, and society at large on a collision course with corporate decision-makers, who would have to choose between ambitious commitments to reduce their emissions and their bottom lines. Civil society would be unforgiving of investors and companies they believe are moving too slowly. Oil and gas firms, airlines, carmakers, and meat producers would feel the heat. Disruption to supply chains would be a meaningful risk. Investors would reduce exposures to carbon intensive industries, sending asset prices lower. All this as global warming would make natural disasters more likely, more frequent, and more severe.

In January, risk #7 described how climate change would put governments, investors, and society at large on a collision course with corporate decision-makers, who would have to choose between ambitious commitments to reduce their emissions and their bottom lines. Civil society would be unforgiving of investors and companies they believe are moving too slowly. Oil and gas firms, airlines, carmakers, and meat producers would feel the heat. Disruption to supply chains would be a meaningful risk. Investors would reduce exposures to carbon intensive industries, sending asset prices lower. All this as global warming would make natural disasters more likely, more frequent, and more severe.

The global focus on coronavirus will come at the expense of attention paid to climate change. Environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) investing mandates will become weaker in implementation if not in spirit, as investors and companies pursue recovery and growth above all else. Countries will utilize their fiscal space on targeted measures to blunt the impact of the coronavirus, and whatever is left over for broad fiscal stimulus will only be partially dedicated to “green” projects, and to varying degrees across countries. Further, collapsing oil prices will undercut the competitiveness of cleaner alternative energy sources. With large-scale protest activity diminished because of social distancing, civil society actors will turn to cyber and online tools to apply pressure on companies and governments, most of which will have less appetite and ability to respond to climate change. The immediate risk of a clash between politics and economics over climate change significantly diminishes in the short term, even if the overarching threat of climate change remains as real as ever.

In January, risk #8 detailed how the failure of US policy toward Iran, Iraq, and Syria—the major Shia-led nations in the Middle East—would create significant risks for regional stability. These included a lethal conflict with Iran; upward pressure on oil prices; an Iraq caught between Iran's orbit and state failure; and a rogue Syria fused to Russia and Iran. Neither Trump nor Iran's leaders want all-out war, we argued, but deadly skirmishes inside Iraq between US and Iranian forces are probable. The likelihood would increase that the Iraqi government would expel US troops this year, and popular resistance from some Iraqis against Iran's influence there would strain the Iraqi state—OPEC's second-largest oil producer. Feckless US policy in Syria would also drive regional risk in 2020.

In January, risk #8 detailed how the failure of US policy toward Iran, Iraq, and Syria—the major Shia-led nations in the Middle East—would create significant risks for regional stability. These included a lethal conflict with Iran; upward pressure on oil prices; an Iraq caught between Iran's orbit and state failure; and a rogue Syria fused to Russia and Iran. Neither Trump nor Iran's leaders want all-out war, we argued, but deadly skirmishes inside Iraq between US and Iranian forces are probable. The likelihood would increase that the Iraqi government would expel US troops this year, and popular resistance from some Iraqis against Iran's influence there would strain the Iraqi state—OPEC's second-largest oil producer. Feckless US policy in Syria would also drive regional risk in 2020.

The coronavirus outbreak will weaken Iran, Iraq, and Syria. That will lessen the threat of US military conflict with Iran but amplify the effects of failed US policy on the latter two nations and the region. Iran is struggling to confront one of the world's largest outbreaks of coronavirus. Tehran wasn't looking for war with the US before the coronavirus and certainly does not want one now. But it will continue making trouble in the region and wage a public relations battle against Washington's refusal to meaningfully ease sanctions in the face of a humanitarian crisis. As we wrote in January, ill-conceived US policy has been a cause of instability across the region. Iraq is now even more at risk of state failure—with a collapse in oil prices and without a government—and could be pushed over the cliff by an outbreak there. That would be a boon for a resurgent Islamic State and potentially force the US to abandon ship. Syrian reconstruction will also suffer, both if there's an outbreak of the coronavirus and because regional capital will become more constrained as a result of sharply lower oil prices.

In January, risk #9 described how Latin American societies had become increasingly polarized in recent years. In 2020, public anger over sluggish growth, corruption, and low-quality public services would keep the risk of political instability high. This comes at a time when vulnerable middle classes are expecting more state spending on social services, reducing the ability of government to undertake austerity measures expected by foreign investors and the IMF. We expected protests to spread, fiscal balances to deteriorate, antiestablishment politicians to grow stronger, and election outcomes to become less predictable.

In January, risk #9 described how Latin American societies had become increasingly polarized in recent years. In 2020, public anger over sluggish growth, corruption, and low-quality public services would keep the risk of political instability high. This comes at a time when vulnerable middle classes are expecting more state spending on social services, reducing the ability of government to undertake austerity measures expected by foreign investors and the IMF. We expected protests to spread, fiscal balances to deteriorate, antiestablishment politicians to grow stronger, and election outcomes to become less predictable.

Latin America is one of the least-prepared parts of the world to deal with the coronavirus. Serious outbreaks across the region, in conjunction with the oil price collapse, will further stoke the voter anger described in our January report. All the problems we predicted will become more likely: fiscal balances will deteriorate, currencies will plummet, anger with governments will rise, public services will fray, and investment flows will diminish. In turn, discontent will reduce governments' ability to undertake needed austerity measures in some countries and further reduce the fiscal space needed to appease protesters in others (for example, Chile). Amid a collapse in oil prices, the leaders of oil-producing countries such as Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, and Mexico will struggle to keep their approval ratings from collapsing. All four also face fiscal constraints. The outlook is particularly bad for Ecuador (and Argentina, though for reasons aside from oil); in Brazil, reforms will still advance, though at a more erratic pace, while in Mexico a poorly functioning government will worsen the crisis.

In January, risk #10 described how President Recep Tayyip Erdogan—who has a long history of provocative behavior in response to threats, sparking confrontation with both foreign and domestic critics—has entered a period of steep political decline. He's suffering defections from the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) as popular former allies establish new parties. His ruling coalition is shaky. Relations with the US would hit new lows, we forecasted, as likely US sanctions take effect in the first half of this year, undermining the country's reputation and investment climate and putting further pressure on the lira. Erdogan's responses to these various challenges would further damage Turkey's ailing economy, we warned.

In January, risk #10 described how President Recep Tayyip Erdogan—who has a long history of provocative behavior in response to threats, sparking confrontation with both foreign and domestic critics—has entered a period of steep political decline. He's suffering defections from the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) as popular former allies establish new parties. His ruling coalition is shaky. Relations with the US would hit new lows, we forecasted, as likely US sanctions take effect in the first half of this year, undermining the country's reputation and investment climate and putting further pressure on the lira. Erdogan's responses to these various challenges would further damage Turkey's ailing economy, we warned.

A serious coronavirus outbreak in Turkey would put Erdogan even more on the defensive and leave him even more prone to erratic policymaking. He would dive deeper into unorthodox economic policies. Cheap oil gives Turkey's central bank the scope to cut interest rates into single digits, as Erdogan has long desired. But it also leaves the country with limited monetary policy capacity to fight economic fallout from the coronavirus, as real rates in Turkey are already negative. The coronavirus will damage tourism, as well as electronics, pharmaceutical, and automotive exports at a time when portfolio inflows are slowing. On the other hand, falling oil prices will help lower inflation and harm Turkey's opponents, Saudi Arabia and the UAE, more than Turkey and its ally, Qatar. Amid the challenges, Turkey will continue to muddle through, but economic headwinds and the defection of more former AKP allies to new opposition parties—most recently former deputy prime minister Ali Babacan—will render Erdogan a wounded and unpredictable leader.

Red HerringsIn January, we described how the new “Axis of evil”—Iran, North Korea, Venezuela, and Syria—was unlikely to blow up in 2020, despite the headlines. Iran represents the biggest threat, but neither Trump nor Tehran want all-out war.

Iran, North Korea, Syria, and Venezuela remain adamantly anti-American, but war with the US this year is now an even more distant possibility. Facing a domestic public health crisis, Trump's inclination toward military adventures against these countries is even less than before. And none of these states will likely seek a confrontation.

Still a herring

Populist policies in the developed world

In January, we argued that the world's advanced industrial democracies (the US, Europe, and Japan) remain well-positioned to withstand the populist storm this year.

The coronavirus has strained public confidence in government in many countries, but it doesn't herald a populist resurgence with major near-term policy implications in the US, Europe, or Japan. This is an absolutely critical point as we look ahead to the global economic and political system in the eventual aftermath of the pandemic. In the US, the outbreak will increase pressure for universal health care, although these demands will be funneled through Biden's decidedly establishment candidacy. The EU has acted pragmatically during the crisis, undercutting populist campaigns against Brussels. Given the possibility he could be forced to cancel the Olympics, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is under some of the greatest near-term pressure, but his departure wouldn't markedly change governance for Japan.

Still a herring

Post-Brexit

In January, we described how a big win for Prime Minister Boris Johnson and his Conservative Party, and an historic loss for Jeremy Corbyn's Labour Party, gives the UK a much-needed break from Brexit madness in 2020.

The coronavirus outbreak has added complications to already messy negotiations between the UK and the EU. The coronavirus means limited face-to-face talks, and it may weaken the UK government's commitment to its “divergence” agenda over fears that UK business would face added bureaucratic burdens on top of coronavirus effects (not to mention that Johnson will be politically weaker for having badly mismanaged the crisis). Nevertheless, a narrow UK-EU goods deal or a prolongation of the talks remain the most likely outcome, meaning 2020 in the UK is still a red herring.

Still a herring ... just

ConclusionIt's important to recognize the unprecedented nature of this environment in the context of our experience over recent decades. In the coming weeks the world will get a much better handle on the epidemiology of the coronavirus pandemic, but the fractiousness and weakness of the geopolitical order—in terms of the legitimacy of domestic politics, the weakness of existing international alliances, and the lack of alignment of institutional frameworks and today's global balance of power—reflect a radically different backdrop for a global crisis than any we've experienced in recent decades. Looking forward, it also implies a different trajectory for the world order as we know it, when we eventually come out the other side.

Yours through the looking glass,

—Ian & Cliff

.jpg)