We're done with the pandemic. It's not yet done with us. The finish line depends on where you live. Critically, China's zero-Covid policy will fail.

In the developed world, the end is near. You wouldn't think so, given the explosion of cases of the newly dominant and highly transmissible Omicron variant. But those record levels of infections are encountering highly vaccinated populations—bolstered by the most effective mRNA vaccines and, soon, a rapid rollout of Covid treatments that severely minimize the risk of hospitalization and death. That means the pandemic becomes endemic for advanced industrial economies by the end of the first quarter. Even in the developed world, the economic hangover from the pandemic will endure with disrupted supply chains and persistent inflation. A more deadly variant emerging remains a tail risk, but it would still pose much less danger given the tools available to fight it (much as Omicron would've felt apocalyptic if it had hit the world pre-vaccines, a year earlier).

But most countries will have a harder time—and not just because of Omicron.

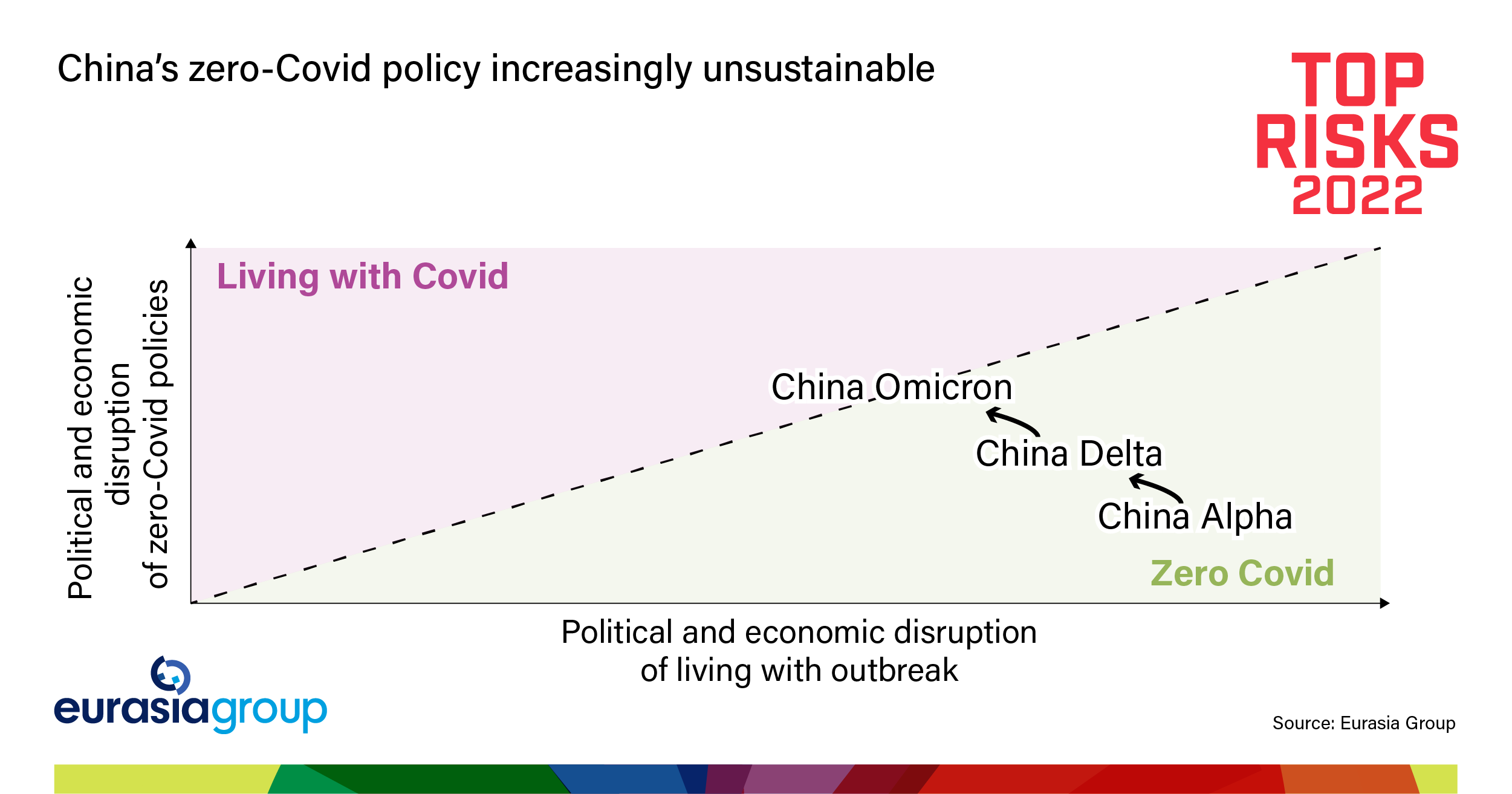

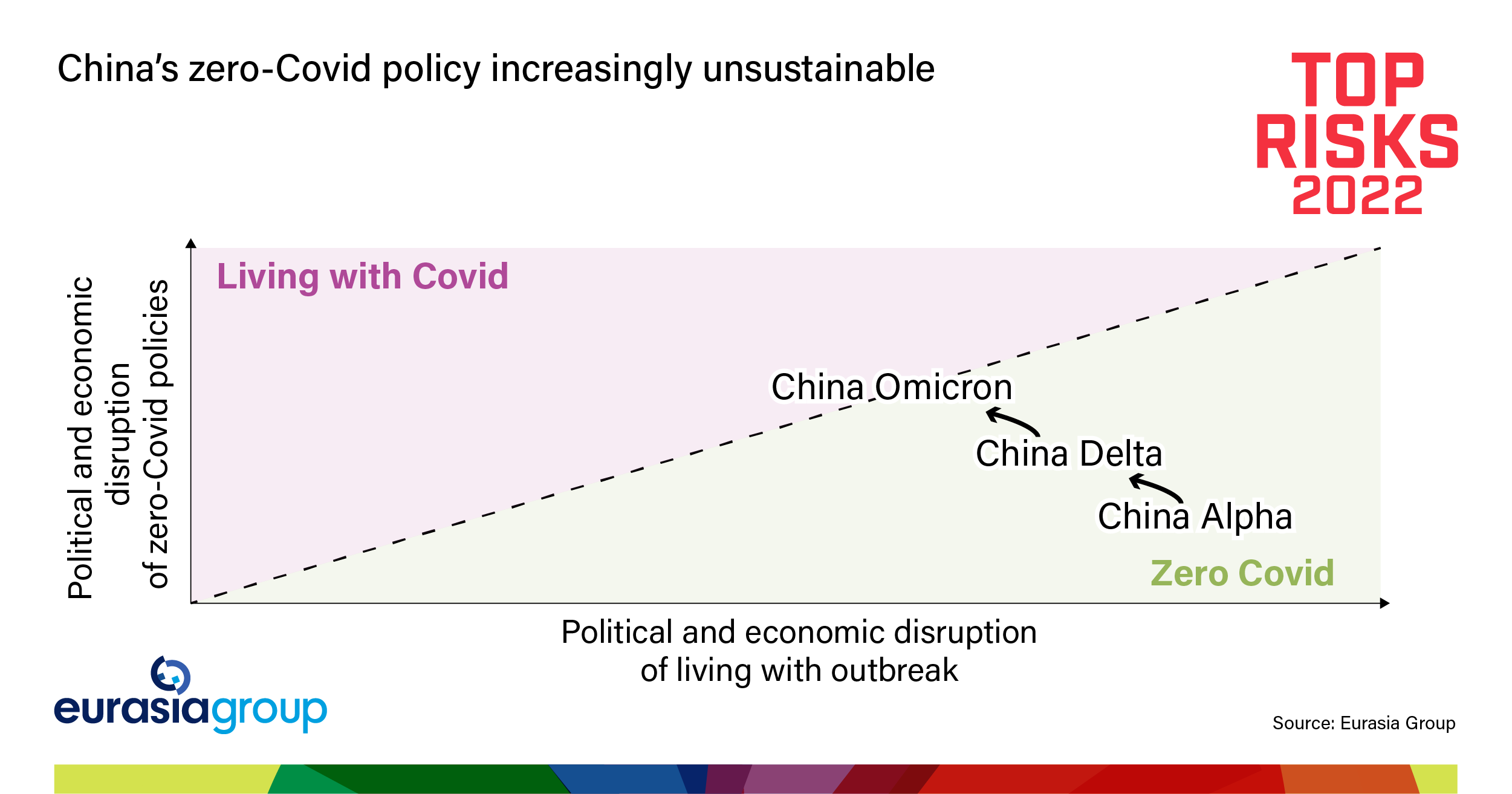

China is in the most difficult situation because of a zero-Covid policy that looked incredibly successful in 2020 (please see Risk #4), but now has become a fight against a much more transmissible variant with broader lockdowns and vaccines with limited effectiveness. And the population has virtually no antibodies against Omicron. Keeping the country locked down for two years has now made it more risky to open it back up. It's the opposite of where Xi wants his country to be in the run-up to his third term, but there's nothing he can do about it: The initial success of zero Covid and Xi's personal attachment to it makes it impossible to change course.

The initial success of China's zero-Covid policy and Xi's personal attachment to it makes it impossible to change course

China's policy will fail to contain infections, leading to larger outbreaks, requiring in turn more severe lockdowns. This will in turn lead to greater economic disruptions, more state intervention, and a more dissatisfied population at odds with the triumphalist “China defeated Covid” mantra of the state-run media. The country will be stuck in this position at least until it can roll out domestically developed mRNA shots and boosters across the population—at the end of the year by the earliest. That means a particularly tough time for what pre-Covid had become the world's primary engine for growth.

China's problems add to the disruption of supply chains, which will present ongoing risks across the world. Shipping constraints, Covid-19 outbreaks, and shortages of staff, raw material, and equipment—all more acute because of China's zero-Covid policy—will make goods less available. High prices for shipping will also hurt small- and medium-sized businesses that don't have the resources to book containers, let alone their own ships. Supply constraints should recede over the course of 2022, but disruptions will persist in many sectors. Midyear contract negotiations at major US ports and related slowdowns will add to the difficulties. These supply-chain problems will prompt governments to step in, but state intervention could make things worse by further distorting markets and delaying incentives for adjustment.

Also on the economic side, persistent, high inflation will be an overarching economic and political challenge. Citizens are still enduring lockdowns, shutdowns, sacrifice, and anxiety—while food and gas prices have soared. Pent-up demand, supply-chain disruptions, and labor shortages caused mainly by the pandemic are all driving prices higher. This will create problems for central banks, which have to balance an imperative to facilitate the economic recovery with the need to contain rising prices. Already, many emerging market central banks are being pressed to raise interest rates to stem a rise in inflation (and expectations of more). Leading industrial country central banks are also pivoting toward tighter policy. Higher inflation breeds inequality, feeding economic insecurity and public discontent.

Omicron will widen the broader gap between developing and developed markets. The vaccines that have mostly been used in emerging markets offer little protection against infection and less ability than mRNA vaccines to protect against severe illness and death. Only 8% of people in low-income countries have received at least one shot, leaving them vulnerable. The demand for booster shots in developed countries will prevent the most effective vaccines from becoming more widely available in many emerging markets, so even those who are vaccinated will not have lasting protection. That will deepen a sense of injustice in the developing world.

Continued outbreaks will mean growth in many emerging markets will disappoint, creating a permanent gap in trajectory compared to advanced industrial democracies that further widens global inequality. Many emerging markets responded to the pandemic with one-off programs that expanded the safety net without aiding longer-run recoveries. These emerging markets now face the worst of both worlds: limited fiscal space for more spending as outbreaks continue and large imbalances left on state balance sheets. With global financing costs on the rise in 2022, they will find it increasingly hard to finance higher debt levels and continued large deficits—creating conditions for a so-called debt bomb. While the trigger for a crisis is uncertain, higher interest rates and less available capital will inflict financial distress in many developing countries and some will need to reschedule debt payments. Aside from Turkey, already in the midst of a currency crisis (please see Risk #10), the most vulnerable countries include some in Latin America as well as Sri Lanka and Tunisia.

Low growth, high inflation, and growing inequality will exacerbate public frustration with governments and stoke political instability to a degree we haven't seen since the 1990s. This will be reflected in sharp shifts toward anti-incumbent voting behavior (Brazil, Argentina) and heterodox policymaking (Turkey). Countries that had experienced sharp decreases in inequality in the leadup to the pandemic are more vulnerable to the political effects of the latest spike in inequality. These include Chile, Colombia, Thailand, Brazil, the Philippines, and Tunisia.

Two years after it began to spread in China, the virus continues to wreak havoc ... and the most successful policy battling the virus has become the least.