The global inflation shock that began in the United States in 2021 and took hold worldwide in 2022 will have powerful economic and political ripple effects in 2023. It will be the principal driver of global recession, add to financial stress, and stoke social discontent and political instability everywhere.

Today's historically high inflation comes from multiple sources. First was the Covid-19 pandemic, which prompted governments to cushion the fall in incomes with extraordinary fiscal and monetary stimulus at the same time that it disrupted global supply. Then, just as the United States and Europe were coming out of the pandemic thanks to vaccines, China doubled down on its zero-Covid policy, locking down the global economy's most important manufacturing and shipping hubs. Finally, Russia's invasion of Ukraine and the West's sanctions in response put a strain on the global supply of energy, food, and fertilizer.

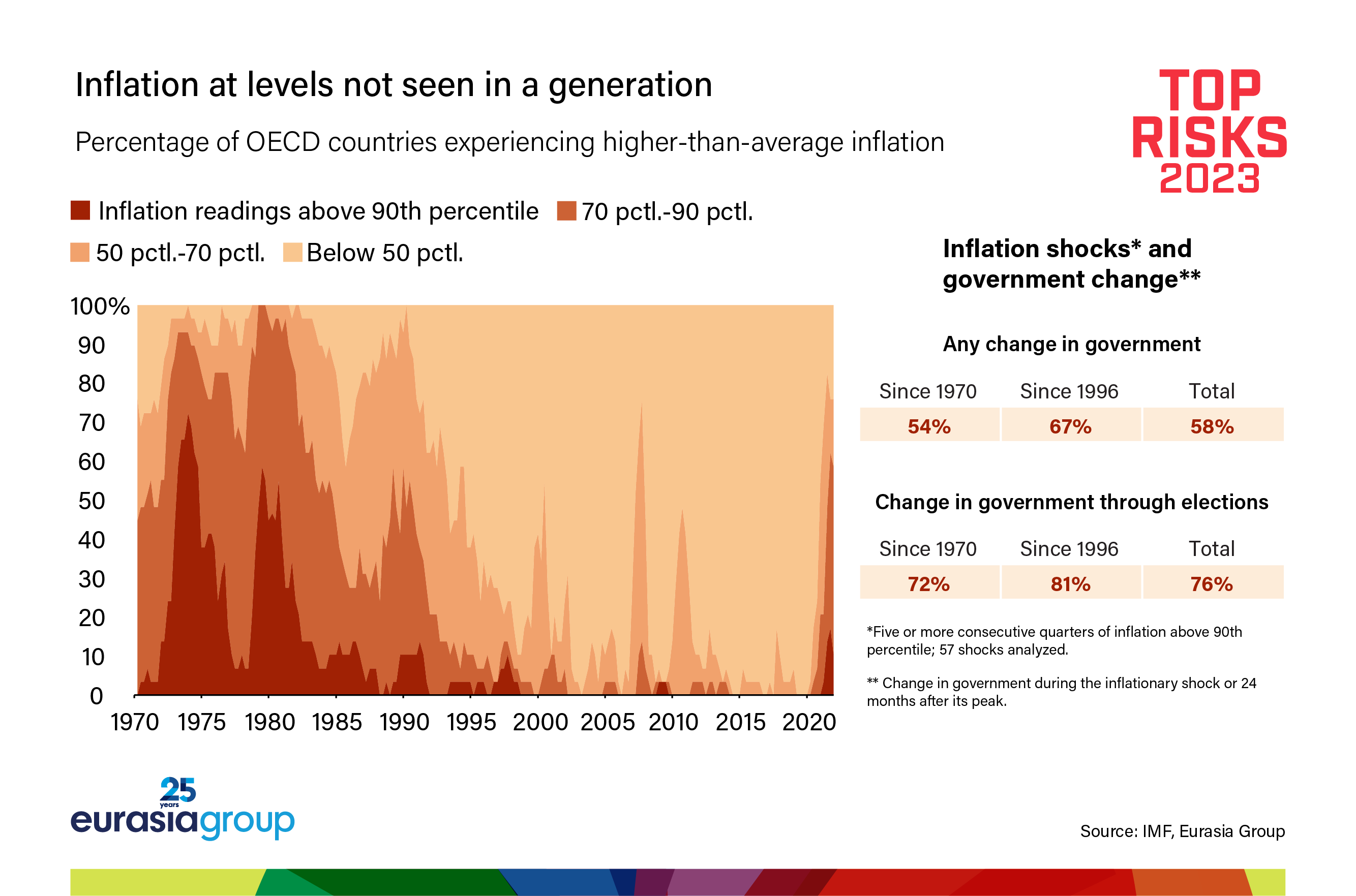

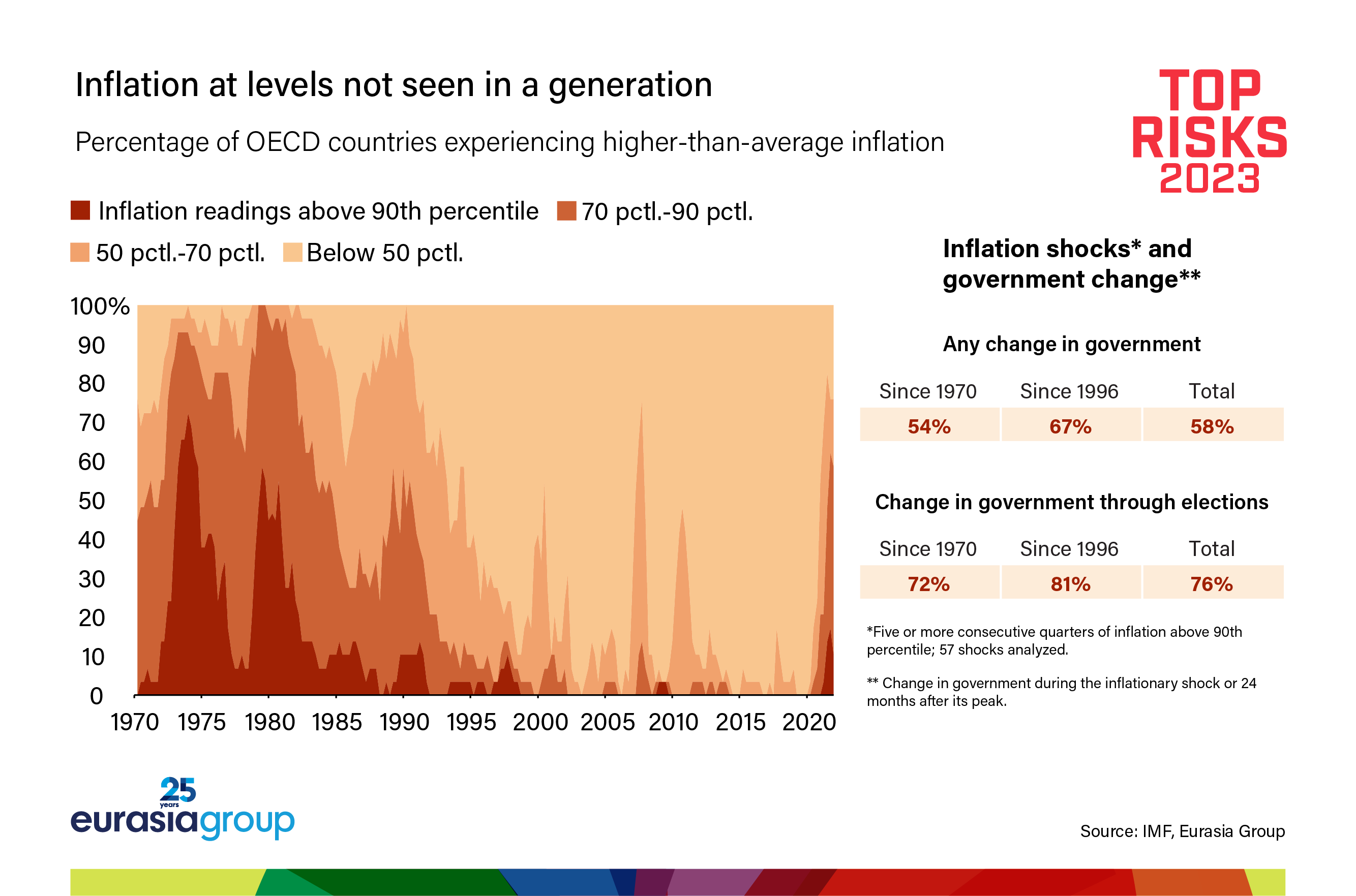

This unprecedented confluence of overlapping shocks pushed inflation to levels most countries hadn't seen in nearly 50 years. At first, central bankers believed the mounting price pressures would be “transitory” and kept policy too loose for too long. Once they realized their mistake, they were forced to respond to prevent inflation expectations from becoming unmoored. The US Federal Reserve took the lead with aggressive interest rate hikes and balance-sheet reduction in 2022, prompting others to follow suit.

Though the end of the tightening cycle is now in sight, central banks will maintain a restrictive policy stance through much of 2023, undermining global demand. And global credit and financial conditions will continue to tighten beyond this year as past rate hikes work their way through the financial system with a lag.

But inflation will prove sticky despite rapidly rising interest rates, driven by continued supply chain constraints and lingering pandemic-era “excess savings”—but also, critically, by persistently high energy prices caused by the war in Ukraine (please see risk #6) that can't be countered by monetary policy.

With tightening credit and financial conditions at a time of still-high inflation, households and companies will feel the pinch. Wary of adding fuel to the inflation fire and facing rising interest costs, policymakers in credit-worthy advanced economies will try to absorb the income risk for households and relieve cost pressures on businesses through costly energy market interventions and subsidies financed by public debt. But in some advanced economies such as the United Kingdom and Italy, and in most developing markets, comprehensive and long-lasting fiscal support measures will be too expensive. As a result, households and companies will see their real incomes erode.

The combination of high inflation, rising interest rates, and insufficient fiscal support will push the global economy into recession. The global downturn will be compounded by uncertainty in China's economic rebound post-zero Covid (please see risk #2) and Europe's painful transition to living without Russian energy. With consumer and business confidence weakening, global growth will slow from 6% in 2021 to about 3% in 2022 to less than 2% in 2023, with much of the world experiencing negative growth. While the absence of financial imbalances of the scale witnessed in 2008 or 2020 will limit the depth of the downturn, without a boost from expansionary monetary and fiscal policy, the recession will prove protracted.

One immediate effect of these economic troubles will be pressure on incumbents in countries with elections this year: Turkey, Spain, Argentina, Nigeria, and Poland. But even countries where elections are not scheduled will see greater risk of government turnover. And where governments muddle through, popular pressure for fiscally unsustainable policies in a tight financial environment will exacerbate debt problems and could trigger market instability—for example, in the UK, Italy, Brazil, Colombia, and Hungary.

Rising interest rates and global recession will also raise the risk of emerging-market crises. The nightmare scenario is a sudden stop in capital flows to emerging markets as we saw in the early 1980s, 1997, and 2008, prompted by a collapse in risk appetite that causes capital flight to the United States. These sorts of crises take much longer to happen than expected … and then happen very suddenly. The resulting currency depreciation would make it hard for countries to service their dollar-denominated debts and to afford imports of food, energy, and other necessities. Lower income commodity importers with high levels of foreign-currency debt and fixed exchange rates or low foreign exchange reserves such as Pakistan and Egypt are especially vulnerable to balance-of-payments, debt, and banking crises. But even rich countries that borrow in their own currencies, such as the UK and Japan, are in danger from rapid depreciations that leave them unable to afford imports and vulnerable to financial stress.

In the unlikely-but-plausible event of a systemic financial crisis, global policy coordination will be lacking. Neither geopolitics nor domestic politics are in the same place they were in 2008, when the world's largest economies came together at the G20 to avert disaster. Consumed by domestic challenges, creditor nations have little appetite for multilateral debt restructuring and relief, and international financial institutions such as the IMF could fill only part of the resulting financing gaps. Several countries would be forced to make the difficult decision to default on their debts, further weakening global growth, fueling social unrest, and disrupting politics.